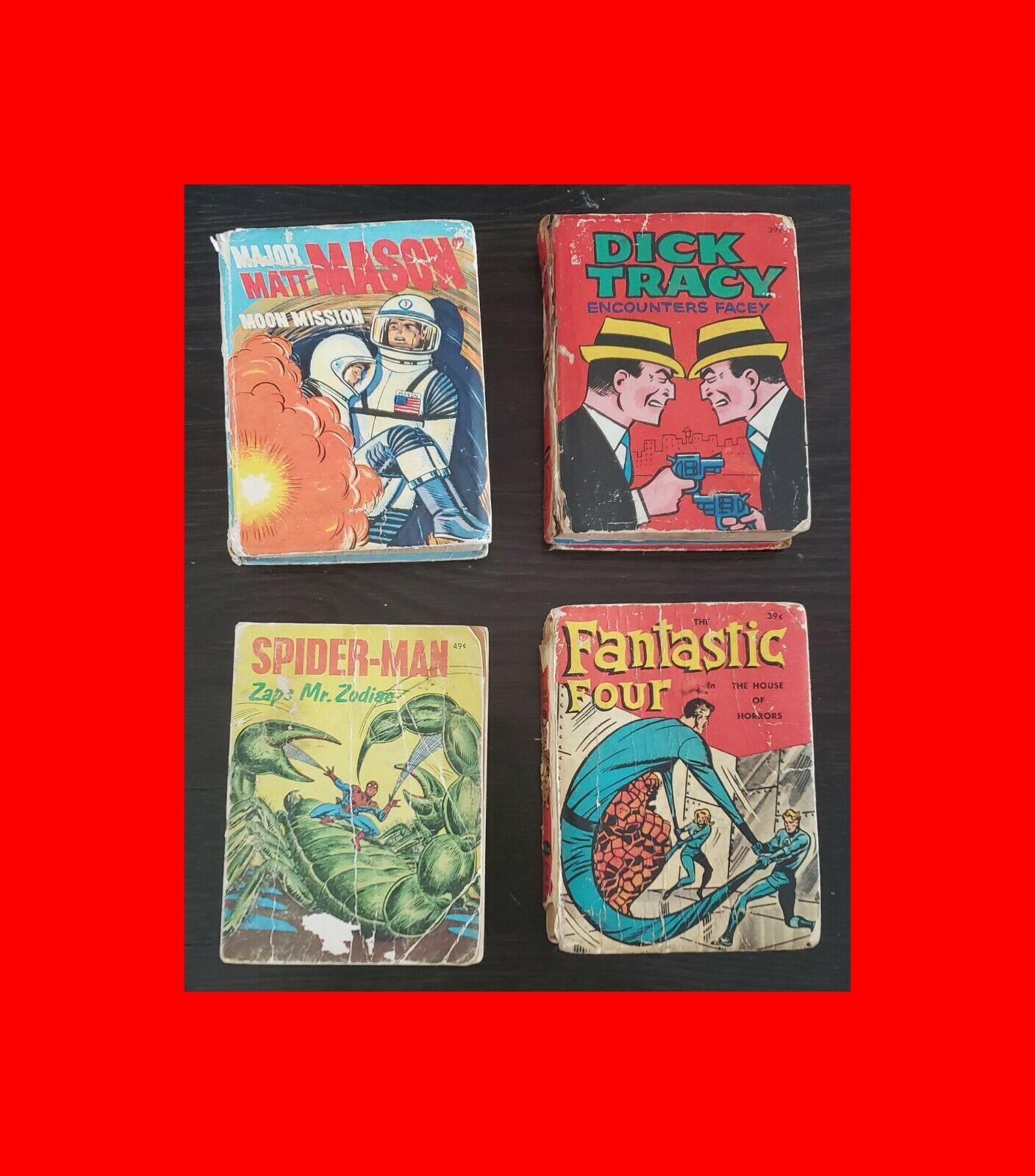

?4 FAIR MINI BOOK LOT:COMIC-SPIDERMAN/FANTASTIC FOUR/DICK TRACY/MAJOR MATT MASON

$

24

Description

4 FAIR SMALL HC BOOK LOT:COMIC-SPIDER-MAN/FANTASTIC FOUR/DICK TRACY/MAJOR MATT MASON MOON MISSION

Each small book is 5" x 3.75". Major Matt Mason and Spider-Man are in in pretty good old book condition, Fantastic Four and Dick Trscy not so good, rough shape still in 1 piece. Good news is the better condition ones, Major Matt Mason and Spider-Man, are there more valuable books in the lot anyway.

1) Spider Man Zaps Mr. Zodiac Illustrated2) Dick Tracy Encounters Facey (Whitman Big Little Book)3) Major Matt Mason : Moon Mission4) The Fantastic Four in the house of horrors (A big little book) YOU GET THESE 4 BOOKS:1) George S. ElrickSpider Man Zaps Mr. Zodiac Illustrated

Whitman , A Big Little Book Marvel Comics Group , 1976 5779-2

Features & details

Product information

PublisherWestern Publ. Co.Publication dateJanuary 1, 1976LanguageEnglishShipping Weight6.4 ouncesBook length248-----2) Paul S. NewmanDick Tracy Encounters Facey (Whitman Big Little Book)

Product information

PublisherWhitmanPublication dateJanuary 1, 1967Package Dimensions9 x 6 x 1 inchesShipping Weight1.38 pounds------3) Major Matt Mason : Moon Mission / by George S. ElrickDescription

An old collectors item!

Features & details

Product information

PublisherRacine, Wisconsin : Whitman Publishing Co., c1968Publication dateJanuary 1, 1968-----4) William JohnstonThe Fantastic Four in the house of horrors (A big little book)

Whitman Big Little 1968 hardcover

Features & details

Product information

PublisherWhitmanPublication dateJanuary 1, 1968LanguageEnglishPackage Dimensions9.1 x 6.6 x 1.1 inchesShipping Weight1.58 poundsBook length248

----SOME GENERAL INFO ABOUT Spider-Man

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Peter Parker" redirects here, For other uses, see Peter Parker (disambiguation),

This article is about the superhero, For other uses, see Spider-Man (disambiguation),

Spider-Man

From The Amazing Spider-Man #547 (March 2008)

Art by Steve McNiven and Dexter Vines

Publication information

Publisher Marvel Comics

First appearance Amazing Fantasy #15 (Aug, 1962)

Created by Stan Lee

Steve Ditko

In-story information

Alter ego Peter Benjamin Parker

Species Human Mutate

Team affiliations Daily Bugle

Front Line

New Fantastic Four

Avengers

New Avengers

Future Foundation

Heroes for Hire

Partnerships Venom

Scarlet Spider

Wolverine

Human Torch

Daredevil

Black Cat

Punisher

Toxin

Iron Man

Ms, Marvel

Notable aliases Ricochet, Dusk, Prodigy, Hornet, Ben Reilly/Scarlet Spider

Abilities

Superhuman strength, speed, agility, stamina, reflexes, and endurance

Regenerative healing factor

Ability to cling to most surfaces

Able to shoot extremely strong spider-web strings from wrists

Precognitive Spider-Sense

Genius-level intellect

Master hand-to-hand combatant

Spider-Man is a fictional character, a comic book superhero who appears in comic books published by Marvel Comics, Created by writer-editor Stan Lee and writer-artist Steve Ditko, he first appeared in Amazing Fantasy #15 (August 1962), Lee and Ditko conceived the character as an orphan being raised by his Aunt May and Uncle Ben, and as a teenager, having to deal with the normal struggles of adolescence in addition to those of a costumed crimefighter, Spider-Man's creators gave him super strength and agility, the ability to cling to most surfaces, shoot spider-webs using devices of his own invention which he called "web-shooters", and react to danger quickly with his "spider-sense", enabling him to combat his foes,

When Spider-Man first appeared in the early 1960s, teenagers in superhero comic books were usually relegated to the role of sidekick to the protagonist, The Spider-Man series broke ground by featuring Peter Parker, a teenage high school student and person behind Spider-Man's secret identity to whose "self-obsessions with rejection, inadequacy, and loneliness" young readers could relate,[1] Unlike previous teen heroes such as Bucky and Robin, Spider-Man did not benefit from being the protégé of any adult superhero mentors like Captain America and Batman, and thus had to learn for himself that "with great power there must also come great responsibility"—a line included in a text box in the final panel of the first Spider-Man story, but later retroactively attributed to his guardian, the late Uncle Ben,

Marvel has featured Spider-Man in several comic book series, the first and longest-lasting of which is titled The Amazing Spider-Man, Over the years, the Peter Parker character has developed from shy, nerdy high school student to troubled but outgoing college student, to married high school teacher to, in the late 2000s, a single freelance photographer, his most typical adult role, As of 2011, he is additionally a member of the Avengers and the Fantastic Four, Marvel's flagship superhero teams, In the comics, Spider-Man is often referred to as "Spidey", "web-slinger", "wall-crawler", or "web-head",

Spider-Man is one of the most popular and commercially successful superheroes,[2] As Marvel's flagship character and company mascot, he has appeared in many forms of media, including several animated and live-action television shows, syndicated newspaper comic strips, and a series of films st*rring Tobey Maguire as the "friendly neighborhood" hero in the first three movies, Andrew Garfield has taken over the role of Spider-Man in a reboot of the films,[3] Reeve Carney st*rs as Spider-Man in the 2010 Broadway musical Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark,[4] Spider-Man placed 3rd on IGN's Top 100 Comic Book Heroes of All Time in 2011,[5]

Contents

1 Publication history

1,1 Creation and development

1,2 Commercial success

2 Fictional character biography

2,1 Personality

3 Other versions

4 Powers and equipment

5 Supporting characters

5,1 Enemies

6 Cultural influence

7 In other media

8 Awards and honors

9 See also

9,1 Selected story arcs

10 Notes

11 References

12 External links

Publication history

Creation and development

Richard Wentworth a,k,a, the Spider in the pulp magazine The Spider, Stan Lee stated that it was the name of this character that inspired him to create a character that would become Spider-Man,[6]

In 1962, with the success of the Fantastic Four, Marvel Comics editor and head writer Stan Lee was casting about for a new superhero idea, He said the idea for Spider-Man arose from a surge in teenage demand for comic books, and the desire to create a character with whom teens could identify,[7]:1 In his autobiography, Lee cites the non-superhuman pulp magazine crime fighter the Spider (see also The Spider's Web and The Spider Returns) as a great influence,[6]:130 and in a multitude of print and video interviews, Lee stated he was further inspired by seeing a spider climb up a wall—adding in his autobiography that he has told that story so often he has become unsure of whether or not this is true,[note 1] Looking back on the creation of Spider-Man, 1990s Marvel editor-in-chief Tom DeFalco stated he did not believe that Spider-Man would have been given a chance in today's comics world, where new characters are vetted with test audiences and marketers,[7]:9 At that time, however, Lee had to get only the consent of Marvel publisher Martin Goodman for the character's approval,[7]:9 In a 1986 interview, Lee described in detail his arguments to overcome Goodman's objections,[note 2] Goodman eventually agreed to let Lee try out Spider-Man in the upcoming final issue of the canceled science-fiction and supernatural anthology series Amazing Adult Fantasy, which was renamed Amazing Fantasy for that single issue, #15 (Aug, 1962),[8]:95

Comics historian Greg Theakston says that Lee, after receiving Goodman's approval for the name Spider-Man and the "ordinary teen" concept, approached artist Jack Kirby, Kirby told Lee about an unpublished character on which he collaborated with Joe Simon in the 1950s, in which an orphaned boy living with an old couple finds a magic ring that granted him superhuman powers, Lee and Kirby "immediately sat down for a story conference" and Lee afterward directed Kirby to flesh out the character and draw some pages, Steve Ditko would be the inker,[note 3] When Kirby showed Lee the first six pages, Lee recalled, "I hated the way he was doing it! Not that he did it badly—it just wasn't the character I wanted; it was too heroic",[9]:12 Lee turned to Ditko, who developed a visual style Lee found satisfactory, Ditko recalled:

One of the first things I did was to work up a costume, A vital, visual part of the character, I had to know how he looked ,,, before I did any breakdowns, For example: A clinging power so he wouldn't have hard shoes or boots, a hidden wrist-shooter versus a web gun and holster, etc, ,,, I wasn't sure Stan would like the idea of covering the character's face but I did it because it hid an obviously boyish face, It would also add mystery to the character,,,,[10]

Although the interior artwork was by Ditko alone, Lee rejected Ditko's cover art and commissioned Kirby to pencil a cover that Ditko inked,[11] As Lee explained in 2010, "I think I had Jack sketch out a cover for it because I always had a lot of confidence in Jack's covers,"[12]

In an early recollection of the character's creation, Ditko described his and Lee's contributions in a mail interview with Gary Martin published in Comic Fan #2 (Summer 1965): "Stan Lee thought the name up, I did costume, web gimmick on wrist & spider signal,"[13] At the time, Ditko shared a Manhattan studio with noted fetish artist Eric Stanton, an art-school classmate who, in a 1988 interview with Theakston, recalled that although his contribution to Spider-Man was "almost nil", he and Ditko had "worked on storyboards together and I added a few ideas, But the whole thing was created by Steve on his own,,, I think I added the business about the webs coming out of his hands",[9]:14

Kirby disputed Lee's version of the story, and claimed Lee had minimal involvement in the character's creation, According to Kirby, the idea for Spider-Man had originated with Kirby and Joe Simon, who in the 1950s had developed a character called the Silver Spider for the Crestwood Publications comic Black Magic, who was subsequently not used,[note 4] Simon, in his 1990 autobiography, disputed Kirby's account, asserting that Black Magic was not a factor, and that he (Simon) devised the name "Spider-Man" (later changed to "The Silver Spider"), while Kirby outlined the character's story and powers, Simon later elaborated that his and Kirby's character conception became the basis for Simon's Archie Comics superhero the Fly, Artist Steve Ditko stated that Lee liked the name Hawkman from DC Comics, and that "Spider-Man" was an outgrowth of that interest,[10]

Simon concurred that Kirby had shown the original Spider-Man version to Lee, who liked the idea and assigned Kirby to draw sample pages of the new character but disliked the results—in Simon's description, "Captain America with cobwebs",[note 5] Writer Mark Evanier notes that Lee's reasoning that Kirby's character was too heroic seems unlikely—Kirby still drew the covers for Amazing Fantasy #15 and the first issue of The Amazing Spider-Man, Evanier also disputes Kirby's given reason that he was "too busy" to also draw Spider-Man in addition to his other duties since Kirby was, said Evanier, "always busy",[14]:127 Neither Lee's nor Kirby's explanation explains why key story elements like the magic ring were dropped; Evanier states that the most plausible explanation for the sudden change was that Goodman, or one of his assistants, decided that Spider-Man as drawn and envisioned by Kirby was too similar to the Fly,[14]:127

Author and Ditko scholar Blake Bell writes that it was Ditko who noted the similarities to the Fly, Ditko recalled that, "Stan called Jack about the Fly", adding that "[d]ays later, Stan told me I would be penciling the story panel breakdowns from Stan's synopsis", It was at this point that the nature of the strip changed, "Out went the magic ring, adult Spider-Man and whatever legend ideas that Spider-Man story would have contained", Lee gave Ditko the premise of a teenager bitten by a spider and developing powers, a premise Ditko would expand upon to the point he became what Bell describes as "the first work for hire artist of his generation to create and control the narrative arc of his series", On the issue of the initial creation, Ditko states, "I still don't know whose idea was Spider-Man",[15] Kirby noted in a 1971 interview that it was Ditko who "got Spider-Man to roll, and the thing caught on because of what he did",[16] Lee, while claiming credit for the initial idea, has acknowledged Ditko's role, stating, "If Steve wants to be called co-creator, I think he deserves [it]",[17] Writer Al Nickerson believes "that Stan Lee and Steve Ditko created the Spider-Man that we are familiar with today [but that] ultimately, Spider-Man came into existence, and prospered, through the efforts of not just one or two, but many, comic book creators",[18]

In 2008, an anonymous donor bequeathed the Library of Congress the original 24 pages of Ditko art of Amazing Fantasy #15, including Spider-Man's debut and the stories "The Bell-Ringer", "Man in the Mummy Case", and "There Are Martians Among Us",[19]

Commercial success

Amazing Fantasy #15 (Aug, 1962), The issue that first introduced the fictional character, It was a gateway to the commercial success to the superhero and inspired the launch of The Amazing Spider-Man comics, Cover art by Jack Kirby (penciller) and Steve Ditko (inker),[8]

The character first appeared in Amazing Fantasy #15 which was published in June 1962 (though with a cover date of August),[20] A few months after Spider-Man's introduction in Amazing Fantasy #15 (Aug, 1962), publisher Martin Goodman reviewed the sales figures for that issue and was shocked to find it to have been one of the nascent Marvel's highest-selling comics,[8]:97 A solo ongoing series followed, beginning with The Amazing Spider-Man #1 (March 1963), The title eventually became Marvel's top-selling series[1]:211 with the character swiftly becoming a cultural icon; a 1965 Esquire poll of college campuses found that college students ranked Spider-Man and fellow Marvel hero the Hulk alongside Bob Dylan and Che Guevara as their favorite revolutionary icons, One interviewee selected Spider-Man because he was "beset by woes, money problems, and the question of existence, In short, he is one of us,"[1]:223 Following Ditko's departure after issue #38 (July 1966), John Romita, Sr, replaced him as penciler and would draw the series for the next several years, In 1968, Romita would also draw the character's extra-length stories in the comics magazine The Spectacular Spider-Man, a proto-graphic novel designed to appeal to older readers, It only lasted for two issues, but it represented the first Spider-Man spin-off publication, aside from the original series' summer annuals that began in 1964,[21]

An early 1970s Spider-Man story led to the revision of the Comics Code, Previously, the Code forbade the depiction of the use of illegal drugs, even negatively, However, in 1970, the Nixon administration's Department of Health, Education, and Welfare asked Stan Lee to publish an anti-drug message in one of Marvel's top-selling titles,[1]:239 Lee chose the top-selling The Amazing Spider-Man; issues #96–98 (May–July 1971) feature a story arc depicting the negative effects of drug use, In the story, Peter Parker's friend Harry Osborn becomes addicted to pills, When Spider-Man fights the Green Goblin (Norman Osborn, Harry's father), Spider-Man defeats the Green Goblin, by revealing Harry's drug addiction, While the story had a clear anti-drug message, the Comics Code Authority refused to issue its seal of approval, Marvel nevertheless published the three issues without the Comics Code Authority's approval or seal, The issues sold so well that the industry's self-censorship was undercut and the Code was subsequently revised,[1]:239

In 1972, a second monthly ongoing series st*rring Spider-Man began: Marvel Team-Up, in which Spider-Man was paired with other superheroes and villains, From that point on there have generally been at least two ongoing Spider-Man series at any time, In 1976, his second solo series, The Spectacular Spider-Man began running parallel to the main series, A third series featuring Spider-Man, Web of Spider-Man, launched in 1985 to replace Marvel Team-Up, The launch of a fourth monthly title in 1990, the "adjectiveless" Spider-Man (with the storyline "Torment"), written and drawn by popular artist Todd McFarlane, debuted with several different covers, all with the same interior content, The various versions combined sold over 3 million copies, an industry record at the time, Several limited series, one-shots, and loosely related comics have also been published, and Spider-Man makes frequent cameos and guest appearances in other comic series,[1]:279

In 1998 writer-artist John Byrne revamped the origin of Spider-Man in the 13-issue limited series Spider-Man: Chapter One (Dec, 1998 - Oct, 1999), similar to Byrne's adding details and some revisions to Superman's origin in DC Comics' The Man of Steel,[22] At the same time the original The Amazing Spider-Man was ended with issue #441 (Nov, 1998), and The Amazing Spider-Man was rest*rted with vol, 2, #1 (Jan, 1999),[23] In 2003 Marvel reintroduced the original numbering for The Amazing Spider-Man and what would have been vol, 2, #59 became issue #500 (Dec, 2003),[23]

When primary series The Amazing Spider-Man reached issue #545 (Dec, 2007), Marvel dropped its spin-off ongoing series and instead began publishing The Amazing Spider-Man three times monthly, beginning with #546-549 (all January 2008),[24] The three times monthly scheduling of The Amazing Spider-Man lasted until November 2010 when the comic book was increased from 22 pages to 30 pages each issue and published only twice a month, beginning with #648-649 (all November 2010),[25][26] The following year (November 2011) Marvel st*rted publishing Avenging Spider-Man as the first spin-off ongoing series in addition to the still twice monthly The Amazing Spider-Man since the previous ones were cancelled at the end of 2007,[27] To celebrate the 50th anniversary of Spider-Man's first appearance the story "Ends of the Earth" was written by Dan Slott and published in 2012,[28]

Fictional character biography

The spider bite that gave Peter Parker his powers, Amazing Fantasy #15, art by Steve Ditko,

In Forest Hills, Queens, New York City,[29] high school student Peter Parker is a science-whiz orphan living with his Uncle Ben and Aunt May, As depicted in Amazing Fantasy #15 (Aug, 1962), he is bitten by a radioactive spider (erroneously classified as an insect in the panel) at a science exhibit and "acquires the agility and proportionate strength of an arachnid,"[30] Along with super strength, he gains the ability to adhere to walls and ceilings, Through his native knack for science, he develops a gadget that lets him fire adhesive webbing of his own design through small, wrist-mounted barrels, Initially seeking to capitalize on his new abilities, he dons a costume and, as "Spider-Man", becomes a novelty television st*r, However, "He blithely ignores the chance to stop a fleeing thief, [and] his indifference ironically catches up with him when the same criminal later robs and kills his Uncle Ben," Spider-Man tracks and subdues the killer and learns, in the story's next-to-last caption, "With great power there must also come—great responsibility!"[31]

Despite his superpowers, Parker struggles to help his widowed aunt pay rent, is taunted by his peers—particularly football st*r Flash Thompson—and, as Spider-Man, engenders the editorial wrath of newspaper publisher J, Jonah Jameson,[32][33] As he battles his enemies for the first time,[34] Parker finds juggling his personal life and costumed adventures difficult, In time, Peter graduates from high school,[35] and enrolls at Empire State University (a fictional institution evoking the real-life Columbia University and New York University),[36] where he meets roommate and best friend Harry Osborn, and girlfriend Gwen Stacy,[37] and Aunt May introduces him to Mary Jane Watson,[34][38][39] As Peter deals with Harry's drug problems, and Harry's father is revealed to be Spider-Man's nemesis the Green Goblin, Peter even attempts to give up his costumed identity for a while,[40][41] Gwen Stacy's father, New York City Police detective captain George Stacy is accidentally killed during a battle between Spider-Man and Doctor Octopus (#90, Nov, 1970),[42] In the course of his adventures Spider-Man has made a wide variety of friends and contacts within the superhero community, who often come to his aid when he faces problems that he cannot solve on his own,

In issue #121 (June 1973),[34] the Green Goblin throws Gwen Stacy from a tower of either the Brooklyn Bridge (as depicted in the art) or the George Washington Bridge (as given in the text),[43][44] She dies during Spider-Man's rescue attempt; a note on the letters page of issue #125 states: "It saddens us to say that the whiplash effect she underwent when Spidey's webbing stopped her so suddenly was, in fact, what killed her,"[45] The following issue, the Goblin appears to accidentally kill himself in the ensuing battle with Spider-Man,[46]

Working through his grief, Parker eventually develops tentative feelings toward Watson, and the two "become confidants rather than lovers",[47] Parker graduates from college in issue #185,[34] and becomes involved with the shy Debra Whitman and the extroverted, flirtatious costumed thief Felicia Hardy, the Black Cat,[48] whom he meets in issue #194 (July 1979),[34]

From 1984 to 1988, Spider-Man wore a different costume than his original, Black with a white spider design, this new costume originated in the Secret Wars limited series, on an alien planet where Spider-Man participates in a battle between Earth's major superheroes and villains,[49] Not unexpectedly, the change to a longstanding character's iconic design met with controversy, "with many hardcore comics fans decrying it as tantamount to sacrilege, Spider-Man's traditional red and blue costume was iconic, they argued, on par with those of his D,C, rivals Superman and Batman,"[50] The creators then revealed the costume was an alien symbiote which Spider-Man is able to reject after a difficult struggle,[51] though the symbiote returns several times as Venom for revenge,[34]

Parker proposes to Watson in The Amazing Spider-Man #290 (July 1987), and she accepts two issues later, with the wedding taking place in The Amazing Spider-Man Annual #21 (1987)—promoted with a real-life mock wedding using actors at Shea Stadium, with Stan Lee officiating, on June 5, 1987,[52][53] However, David Michelinie, who scripted based on a plot by editor-in-chief Jim Shooter, said in 2007, "I didn't think they actually should [have gotten] married, ,,, I had actually planned another version, one that wasn't used,"[52] In a controversial storyline, Peter becomes convinced that Ben Reilly, the Scarlet Spider (a clone of Peter created by his college professor Miles Warren) is the real Peter Parker, and that he, Peter, is the clone, Peter gives up the Spider-Man identity to Reilly for a time, until Reilly is killed by the returning Green Goblin and revealed to be the clone after all,[54] In stories published in 2005 and 2006 (such as "The Other"), he develops additional spider-like abilities including biological web-shooters, toxic stingers that extend from his forearms, the ability to stick individuals to his back, enhanced Spider-sense and night vision, and increased strength and speed, Peter later becomes a member of the New Avengers, and reveals his civilian identity to the world,[55] furthering his already numerous problems, His marriage to Mary Jane and public unmasking are later erased in the controversial[56] storyline "One More Day", in a Faustian bargain with the demon Mephisto, resulting in several adjustments to the timeline, such as the resurrection of Harry Osborn, the erasure of Parker's marriage, and the return of his traditional tools and powers,[57]

That storyline came at the behest of editor-in-chief Joe Quesada, who said, "Peter being single is an intrinsic part of the very foundation of the world of Spider-Man",[56] It caused unusual public friction between Quesada and writer J, Michael Straczynski, who "told Joe that I was going to take my name off the last two issues of the [story] arc" but was talked out of doing so,[58] At issue with Straczynski's climax to the arc, Quesada said, was

,,,that we didn't receive the story and methodology to the resolution that we were all expecting, What made that very problematic is that we had four writers and artists well underway on [the sequel arc] "Brand New Day" that were expecting and needed "One More Day" to end in the way that we had all agreed it would, ,,, The fact that we had to ask for the story to move back to its original intent understandably made Joe upset and caused some major delays and page increases in the series, Also, the science that Joe was going to apply to the retcon of the marriage would have made over 30 years of Spider-Man books worthless, because they never would have had happened, ,,,[I]t would have reset way too many things outside of the Spider-Man titles, We just couldn't go there,,,,[58]

Personality

"People often say glibly that Marvel succeeded by blending super hero adventure stories with soap opera, What Lee and Ditko actually did in The Amazing Spider-Man was to make the series an ongoing novelistic chronicle of the lead character's life, Most super heroes had problems no more complex or relevant to their readers' lives than thwarting this month's bad guys,,,, Parker had far more serious concern in his life: coming to terms with the death of a loved one, falling in love for the first time, struggling to make a living, and undergoing crises of conscience,"

Comics historian Peter Sanderson[59]

As one contemporaneous journalist observed, "Spider-Man has a terrible identity problem, a marked inferiority complex, and a fear of women, He is anti-social, [sic] castration-ridden, racked with Oedipal guilt, and accident-prone ,,, [a] functioning neurotic",[29] Agonizing over his choices, always attempting to do right, he is nonetheless viewed with suspicion by the authorities, who seem unsure as to whether he is a helpful vigilante or a clever criminal,[60]

Notes cultural historian Bradford W, Wright,

Spider-Man's plight was to be misunderstood and persecuted by the very public that he swore to protect, In the first issue of The Amazing Spider-Man, J, Jonah Jameson, publisher of the Daily Bugle, launches an editorial campaign against the "Spider-Man menace," The resulting negative publicity exacerbates popular suspicions about the mysterious Spider-Man and makes it impossible for him to earn any more money by performing, Eventually, the bad press leads the authorities to brand him an outlaw, Ironically, Peter finally lands a job as a photographer for Jameson's Daily Bugle,[1]:212

The mid-1960s stories reflected the political tensions of the time, as early 1960s Marvel stories had often dealt with the Cold War and Communism,[1]:220-223 As Wright observes,

From his high-school beginnings to his entry into college life, Spider-Man remained the superhero most relevant to the world of young people, Fittingly, then, his comic book also contained some of the earliest references to the politics of young people, In 1968, in the wake of actual militant student demonstrations at Columbia University, Peter Parker finds himself in the midst of similar unrest at his Empire State University,,,, Peter has to reconcile his natural sympathy for the students with his assumed obligation to combat lawlessness as Spider-Man, As a law-upholding liberal, he finds himself caught between militant leftism and angry conservatives,[1]:234-235

Other versions

Main article: Alternative versions of Spider-Man

Due to Spider-Man's popularity in the mainstream Marvel Universe, publishers have been able to introduce different variations of Spider-Man outside of mainstream comics as well as reimagined stories in many other multiversed spinoffs such as Ultimate Spider-Man, Spider-Man 2099, and Spider-Man: India, Marvel has also made its own parodies of Spider-Man in comics such as Not Brand Echh, which was published in the late 1960s and featured such characters as Peter Pooper alias Spidey-Man,[61] and Peter Porker, the Spectacular Spider-Ham, who appeared in the 1980s, The fictional character has also inspired a number of deratives such as a manga version of Spider-Man drawn by Japanese artist Ryoichi Ikegami as well as Hideshi Hino's The Bug Boy, which has been cited as inspired by Spider-Man,[62] Also the French comic Télé-Junior published strips based on popular TV series, In the late 1970s, the publisher also produced original Spider-Man adventures, Artists included Gérald Forton, who later moved to America and worked for Marvel,[63]

Powers and equipment

Main article: Spider-Man's powers and equipment

A bite from a radioactive spider on a school field trip causes a variety of changes in the body of Peter Parker and gives him superpowers,[64] In the original Lee-Ditko stories, Spider-Man has the ability to cling to walls, superhuman strength, a sixth sense ("spider-sense") that alerts him to danger, perfect balance and equilibrium, as well as superhuman speed and agility, Some of his comic series have him shooting webs from his wrists,[64] Brilliant, Parker excels in applied science, chemistry, and physics, The character was originally conceived by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko as intellectually gifted, but not a genius, However, later writers have depicted the character as a genius,[65] With his talents, he sews his own costume to conceal his identity, and constructs many devices that complement his powers, most notably mechanical web-shooters,[64] This mechanism ejects an advanced adhesive, releasing web-fluid in a variety of configurations, including a single rope-like strand to swing from, a net to bind enemies, a single strand for yanking opponents into objects, strands for whipping foreign objects at enemies, and a simple glob to foul machinery or blind an opponent, He can also weave the web material into simple forms like a shield, a spherical protection or hemispherical barrier, a club, or a hang-glider wing, Other equipment include spider-tracers (spider-shaped adhesive homing beacons keyed to his own spider-sense), a light beacon which can either be used as a flashlight or project a "Spider-Signal" design, and a specially modified camera that can take pictures automatically,

Supporting characters

Main article: List of Spider-Man supporting characters

Spider-Man has had a large range of supporting characters introduced in the comics that are essential in the issues and storylines that st*r him, After his parents died, Peter Parker was raised by his loving aunt, May Parker, and his uncle and father figure, Ben Parker, After Uncle Ben is murdered by a burglar, Aunt May is virtually Peter's only family, and she and Peter are very close,[30]

J, Jonah Jameson is depicted as the publisher of the Daily Bugle and is Peter Parker's boss and as a harsh critic of Spider-Man, always saying negative things about the superhero in the newspaper, although his publishing editor and confidant Robbie Robertson is always depicted as a supporter of both Peter Parker and Spider-Man,[32]

Eugene "Flash" Thompson is commonly depicted as Parker's high school tormentor and bully but in some comic issues as a friend as well,[32] Meanwhile Harry Osborn, son of Norman Osborn, is most commonly recognized as Peter's best friend but has also been depicted sometimes as his rival in the comics,[34]

Peter Parker's romantic interests range between his first crush, the fellow high-school student Liz Allan,[32] to having his first date with Betty Brant,[66] the secretary to Daily Bugle newspaper publisher J, Jonah Jameson, After his breakup with Betty Brant, Parker eventually falls in love with his college girlfriend Gwen Stacy,[34][37] daughter of New York City Police Department detective captain George Stacy, both of whom are later killed by supervillain enemies of Spider-Man,[42][42] Mary Jane Watson eventually became Peter's best friend and then his wife,[52] Felicia Hardy, the Black Cat, is a reformed cat burglar who had been Spider-Man's girlfriend and partner at one point,[48]

Enemies

Main article: List of Spider-Man enemies

Writers and artists over the years have established a rogues gallery of supervillains to face Spider-Man, As with him, the majority of these villains' powers originate with scientific accidents or the misuse of scientific technology, and many have animal-themed costumes or powers,[note 6] Early on Spider-Man faced such foes as the Chameleon (introduced in The Amazing Spider-Man #1, March 1963), the Vulture (#2, May 1963), Doctor Octopus (#3, July 1963), the Sandman (#4, Sept, 1963), the Lizard (#6, Nov, 1963), Electro (#9, Feb, 1964), Mysterio (#13, June 1964), the Green Goblin (#14, July 1964), Kraven the Hunter (#15, Aug, 1964),the Scorpion (#20, Jan, 1965), the Rhino (#41, Oct, 1966)—the first original Lee/Romita Spider-Man villain[67]—the Shocker (#46, March 1967), and the physically powerful and well-connected criminal capo Wilson Fisk, also known as the Kingpin,[34] The Clone Saga introduces college professor Miles Warren, who becomes the Jackal, the antagonist of the storyline,[37] After the Green Goblin was presumably killed, a derivative villain called the Hobgoblin was developed to replace him in #238 until Norman was revived later,[68] After Spider-Man rejected his symbiotic black costume, Eddie Brock, a bitter ex-journalist with a grudge against Spider-Man, bonded with the symbiote (which also hated Spider-Man for rejecting it), gaining Spider-Man's powers and abilities, and became the villain Venom in issue #298 (May 1988),[34] Brock briefly became an ally to Spider-Man when Carnage, another symbiote-based villain, went on a murderous spree in issue #344,[69] At times these enemies of Spider-Man have formed groups such as the Sinister Six to oppose Spider-Man,[70] The Green Goblin, Doctor Octopus and Venom are generally described or written as his archenemies,[71][72][73]

Cultural influence

Spider-Man sign appearing in front of The Amazing Adventures of Spider-Man in Universal Studios Florida's Islands of Adventure,

Comic book writer-editor and historian Paul Kupperberg, in The Creation of Spider-Man, calls the character's superpowers "nothing too original"; what was original was that outside his secret identity, he was a "nerdy high school student",[74]:5 Going against typical superhero fare, Spider-Man included "heavy doses of soap-opera and elements of melodrama," Kupperberg feels that Lee and Ditko had created something new in the world of comics: "the flawed superhero with everyday problems," This idea spawned a "comics revolution,"[74]:6 The insecurity and anxieties in Marvel's early 1960s comic books such as The Amazing Spider-Man, The Incredible Hulk, and X-Men ushered in a new type of superhero, very different from the certain and all-powerful superheroes before them, and changed the public's perception of them,[75] Spider-Man has become one of the most recognizable fictional characters in the world, and has been used to sell toys, games, cereal, candy, soap, and many other products,[76]

Spider-Man has become Marvel's flagship character, and has often been used as the company mascot, When Marvel became the first comic book company to be listed on the New York Stock Exchange in 1991, the Wall Street Journal announced "Spider-Man is coming to Wall Street"; the event was in turn promoted with an actor in a Spider-Man costume accompanying Stan Lee to the Stock Exchange,[1]:254 Since 1962, hundreds of millions of comics featuring the character have been sold around the world,[77]

Spider-Man joined the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade from 1987 to 1998 as one of the balloon floats,[78] designed by John Romita Sr,,[79] one of the character's signature artists, A new, different Spider-Man balloon float is scheduled to appear from at least 2009 to 2011,[78]

In 1981, skyscraper-safety activist Dan Goodwin, wearing a Spider-Man suit, scaled the Sears Tower in Chicago, Illinois, the Renaissance Tower in Dallas, Texas, and the John Hancock Center in Chicago, Illinois,[80]

When Marvel wanted to issue a story dealing with the immediate aftermath of the September 11 attacks, the company chose the December 2001 issue of The Amazing Spider-Man,[81] In 2006, Spider-Man garnered major media coverage with the revelation of the character's secret identity,[82] an event detailed in a full page story in the New York Post before the issue containing the story was even released,[83]

In 2008, Marvel announced plans to release a series of educational comics the following year in partnership with the United Nations, depicting Spider-Man alongside UN Peacekeeping Forces to highlight UN peacekeeping missions,[84] A BusinessWeek article listed Spider-Man as one of the top ten most intelligent fictional characters in American comics,[85]

In other media

Tobey Maguire (top) and Andrew Garfield (bottom) have both portrayed Spider-Man on film,

Main article: Spider-Man in other media

Spider-Man has appeared in comics, cartoons, movies, coloring books, novels, records, and children's books,[76] On television, he first st*rred in the ABC animated series Spider-Man (1967-1970)[86] and the CBS live-action series The Amazing Spider-Man (1978–1979), st*rring Nicholas Hammond, Other animated series featuring the superhero include the syndicated Spider-Man (1981–1982), Spider-Man and His Amazing Friends (1981–1983), Fox Kids' Spider-Man (1994–1998), Spider-Man Unlimited (1999–2000), Spider-Man: The New Animated Series (2003), and The Spectacular Spider-Man (2008–2009), A new animated series titled Ultimate Spider-Man premiered on Disney XD on April 1, 2012,[87]

A tokusatsu show featuring Spider-Man was produced by Toei and aired in Japan, It is commonly referred to by its Japanese pronunciation "Supaida-Man",[88] Spider-Man also appeared in other print forms besides the comics, including novels, children's books, and the daily newspaper comic strip The Amazing Spider-Man, which debuted in January 1977, with the earliest installments written by Stan Lee and drawn by John Romita, Sr,[89] Spider-Man has been adapted to other media including games, toys, collectibles, and miscellaneous memorabilia, and has appeared as the main character in numerous computer and video games on over 15 gaming platforms,

Spider-Man was also featured in a trilogy of live-action films directed by Sam Raimi and st*rring Tobey Maguire as the title superhero, The first Spider-Man film was released on May 3, 2002; its sequel, Spider-Man 2, was released on June 30, 2004 and the next sequel, Spider-Man 3, was released on May 4, 2007, A third sequel was originally scheduled to be released in 2011, however Sony later decided to reboot the franchise with a new director and cast, The reboot, titled The Amazing Spider-Man, was released on July 3, 2012; directed by Marc Webb and st*rring Andrew Garfield as the new Spider-Man,[90][91][92][93][94]

A Broadway musical, Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark, began previews on November 14, 2010 at the Foxwoods Theatre on Broadway, with the official opening night on June 14, 2011,[95][96] The music and lyrics were written by Bono and The Edge of the rock group U2, with a book by Julie Taymor, Glen Berger, Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa,[97] Turn Off the Dark is currently the most expensive musical in Broadway history, costing an estimated $70 million,[98] In addition, the show's unusually high running costs are reported to be about $1,2 million per week,[99]

Awards and honors

From the character's inception, Spider-Man stories have won numerous awards, including:

1962 Alley Award: Best Short Story—"Origin of Spider-Man" by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko, Amazing Fantasy #15

1963 Alley Award: Best Comic: Adventure Hero title—The Amazing Spider-Man

1963 Alley Award: Top Hero—Spider-Man

1964 Alley Award: Best Adventure Hero Comic Book—The Amazing Spider-Man

1964 Alley Award: Best Giant Comic - The Amazing Spider-Man Annual #1

1964 Alley Award: Best Hero—Spider-Man

1965 Alley Award: Best Adventure Hero Comic Book—The Amazing Spider-Man

1965 Alley Award: Best Hero—Spider-Man

1966 Alley Award: Best Comic Magazine: Adventure Book with the Main Character in the Title—The Amazing Spider-Man

1966 Alley Award: Best Full-Length Story - "How Green was My Goblin", by Stan Lee & John Romita, Sr,, The Amazing Spider-Man #39

1967 Alley Award: Best Comic Magazine: Adventure Book with the Main Character in the Title—The Amazing Spider-Man

1967 Alley Award Popularity Poll: Best Costumed or Powered Hero—Spider-Man

1967 Alley Award Popularity Poll: Best Male Normal Supporting Character—J, Jonah Jameson, The Amazing Spider-Man

1967 Alley Award Popularity Poll: Best Female Normal Supporting Character—Mary Jane Watson, The Amazing Spider-Man

1968 Alley Award Popularity Poll: Best Adventure Hero Strip—The Amazing Spider-Man

1968 Alley Award Popularity Poll: Best Supporting Character - J, Jonah Jameson, The Amazing Spider-Man

1969 Alley Award Popularity Poll: Best Adventure Hero Strip—The Amazing Spider-Man

1997 Eisner Award: Best Artist/Penciller/Inker or Penciller/Inker Team—1997 Al Williamson, Best Inker: Untold Tales of Spider-Man #17-18

2002 Eisner Award: Best Serialized Story—The Amazing Spider-Man vol, 2, #30–35: "Coming Home", by J, Michael Straczynski, John Romita, Jr,, and Scott Hanna

No date: Empire magazine's fifth-greatest comic book character,[100]

No date: Spider-Man was the #1 superhero on Bravo's Ultimate Super Heroes, Vixens, and Villains show,[101]

No date: Fandomania,com rated him as #7 on their 100 Greatest Fictional Characters list,[102]

See also

United States portal

Comics portal

Speculative fiction portal

Superhero fiction portal

List of Spider-Man titles

Selected story arcs

"Maximum Carnage"

"Identity Crisis"

"The Gathering of Five" and "The Final Chapter"

"One More Day"

"Brand New Day"

"New Ways to Die"

"American Son"

"The Gauntlet and Grim Hunt"

"One Moment in Time"

Notes

^ Lee, Stan; Mair, George (2002), Excelsior!: The Amazing Life of Stan Lee, Fireside, ISBN 0-684-87305-2, "He goes further in his biography, claiming that even while pitching the concept to publisher Martin Goodman, "I can't remember if that was literally true or not, but I thought it would lend a big color to my pitch,""

^ Detroit Free Press interview with Stan Lee, quoted in The Steve Ditko Reader by Greg Theakston (Pure Imagination, Brooklyn, NY; ISBN 1-56685-011-8), p, 12 (unnumbered), "He gave me 1,000 reasons why Spider-Man would never work, Nobody likes spiders; it sounds too much like Superman; and how could a teenager be a superhero? Then I told him I wanted the character to be a very human guy, someone who makes mistakes, who worries, who gets acne, has trouble with his girlfriend, things like that, [Goodman replied,] 'He's a hero! He's not an average man!' I said, 'No, we make him an average man who happens to have super powers, that's what will make him good,' He told me I was crazy",

^ Ditko, Steve (2000), Roy Thomas, ed, Alter Ego: The Comic Book Artist Collection, TwoMorrows Publishing, ISBN 1-893905-06-3, "'Stan said a new Marvel hero would be introduced in #15 [of what became titled Amazing Fantasy], He would be called Spider-Man, Jack would do the penciling and I was to ink the character,' At this point still, 'Stan said Spider-Man would be a teenager with a magic ring which could transform him into an adult hero—Spider-Man, I said it sounded like the Fly, which Joe Simon had done for Archie Comics, Stan called Jack about it but I don't know what was discussed, I never talked to Jack about Spider-Man,,, Later, at some point, I was given the job of drawing Spider-Man'",

^ Jack Kirby in "Shop Talk: Jack Kirby", Will Eisner's Spirit Magazine #39 (February 1982): "Spider-Man was discussed between Joe Simon and myself, It was the last thing Joe and I had discussed, We had a strip called 'The Silver Spider,' The Silver Spider was going into a magazine called Black Magic, Black Magic folded with Crestwood (Simon & Kirby's 1950s comics company) and we were left with the script, I believe I said this could become a thing called Spider-Man, see, a superhero character, I had a lot of faith in the superhero character that they could be brought back,,, and I said Spider-Man would be a fine character to st*rt with, But Joe had already moved on, So the idea was already there when I talked to Stan",

^ Simon, Joe, with Jim Simon, The Comic Book Makers (Crestwood/II, 1990) ISBN 1-887591-35-4, "There were a few holes in Jack's never-dependable memory, For instance, there was no Black Magic involved at all, ,,, Jack brought in the Spider-Man logo that I had loaned to him before we changed the name to The Silver Spider, Kirby laid out the story to Lee about the kid who finds a ring in a spiderweb, gets his powers from the ring, and goes forth to fight crime armed with The Silver Spider's old web-spinning pistol, Stan Lee said, 'Perfect, just what I want,' After obtaining permission from publisher Martin Goodman, Lee told Kirby to pencil-up an origin story, Kirby,,, using parts of an old rejected superhero named Night Fighter,,, revamped the old Silver Spider script, including revisions suggested by Lee, But when Kirby showed Lee the sample pages, it was Lee's turn to gripe, He had been expecting a skinny young kid who is transformed into a skinny young kid with spider powers, Kirby had him turn into,,, Captain America with cobwebs, He turned Spider-Man over to Steve Ditko, who,,, ignored Kirby's pages, tossed the character's magic ring, web-pistol and goggles,,, and completely redesigned Spider-Man's costume and equipment, In this life, he became high-school student Peter Parker, who gets his spider powers after being bitten by a radioactive spider, ,,, Lastly, the Spider-Man logo was redone and a dashing hyphen added",

^ Mondello, Salvatore (March 2004), "Spider-Man: Superhero in the Liberal Tradition", The Journal of Popular Culture X (1): 232–238, doi:10,1111/j,0022-3840,1976,1001_232,x, ",,,a teenage superhero and middle-aged supervillains—an impressive rogues' gallery [that] includes such memorable knaves and grotesques as the Vulture,,,"

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

SOME GENERAL INFO ABOUT Marvel Comics

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the comic book company using that name after 1961, For the earlier comic book series, see Marvel Mystery Comics,

Marvel Comics

Type Subsidiary of Marvel Entertainment

Industry Publishing

Genre Crime, horror, mystery, romance, science fiction, superhero, war, Western

Founded 1939 (as Timely Comics)

Founder(s) Martin Goodman

Headquarters 417 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY

Area served USA, UK

Key people

Axel Alonso, EIC

Dan Buckley, publisher, COO

Stan Lee, former EIC, publisher

Products Comics/See List of Marvel Comics publications

Revenue US$125,7 million (2007)

Operating income US$53,5 million (2007)[1]

Owner(s) Martin Goodman (1939-1968)

Parent Magazine Management Co, (1968-1973)

Cadence Industries (1973-1986)

Marvel Entertainment Group (1986-1997)

Marvel Entertainment (1997- )

Website marvel,com

Marvel Worldwide, Inc,, commonly referred to as Marvel Comics and formerly Marvel Publishing, Inc, and Marvel Comics Group, is an American company that publishes comic books and related media, In 2009, The Walt Disney Company acquired Marvel Entertainment, Marvel Worldwide's parent company,[2] for $4,24 billion,

Marvel st*rted in 1939 as Timely Publications, and by the early 1950s had generally become known as Atlas Comics, Marvel's modern incarnation dates from 1961, with the company later that year launching Fantastic Four and other superhero titles created by Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, and others,

Marvel counts among its characters such well-known properties as Spider-Man, the X-Men, Iron Man, the Hulk, the Fantastic Four, Thor and Captain America; antagonists such as Doctor Doom, the Green Goblin, Magneto, Galactus, and the Red Skull, Most of Marvel's fictional characters operate in a single reality known as the Marvel Universe, with locales set in real-life cities such as New York, Los Angeles and Chicago,[3]

Contents

1 History

1,1 Timely Publications

1,2 Atlas Comics

1,3 1960s

1,4 1970s

1,5 1980s

1,6 1990s

1,7 2000s

2 Officers

2,1 Publishers

2,2 Editors-in-chief

3 Offices

4 Marvel characters in other media

4,1 Films

4,2 Prose novels

4,3 Television programs

4,4 Role-playing games

4,5 Theme parks

4,6 Video games

5 Imprints

5,1 Defunct

6 See also

7 References

8 External links

9 Further reading

History

Timely Publications

Main article: Timely Comics

Marvel Comics #1 (Oct, 1939), the first comic from Marvel precursor Timely Comics, Cover art by Frank R, Paul,

Martin Goodman founded the company later known as Marvel Comics under the name Timely Publications in 1939,[4] publishing comic books under the imprint Timely Comics,[5] Goodman, a pulp magazine publisher who had st*rted with a Western pulp in 1933, was expanding into the emerging—and by then already highly popular—new medium of comic books, Launching his new line from his existing company's offices at 330 West 42nd Street, New York City, New York, he officially held the titles of editor, managing editor, and business manager, with Abraham Goodman officially listed as publisher,[4]

Timely's first publication, Marvel Comics #1 (cover dated Oct, 1939), included the first appearance of Carl Burgos' android superhero the Human Torch, and the first generally available appearance of Bill Everett's anti-hero Namor the Sub-Mariner, among other features, The issue was a great success, with it and a second printing the following month selling, combined, nearly 900,000 copies,[6] While its contents came from an outside packager, Funnies, Inc,, Timely by the following year had its own staff in place,

The company's first true editor, writer-artist Joe Simon, teamed with imminent industry-legend Jack Kirby to create one of the first[citation needed] patriotically themed superheroes, Captain America, in Captain America Comics #1, (March 1941) It, too, proved a major sales hit, with sales of nearly one million,[6]

While no other Timely character would achieve the success of these "big three", some notable heroes—many of which continue to appear in modern-day retcon appearances and flashbacks—include the Whizzer, Miss America, the Destroyer, the original Vision, and the Angel, Timely also published one of humor cartoonist Basil Wolverton's best-known features, "Powerhouse Pepper",[7][8] as well as a line of children's funny-animal comics featuring popular characters like Super Rabbit and the duo Ziggy Pig and Silly Seal,

Goodman hired his wife's cousin,[9] Stanley Lieber, as a general office assistant in 1939,[10] When editor Simon left the company in late 1941,[11] Goodman made Lieber—by then writing pseudonymously as "Stan Lee"—interim editor of the comics line, a position Lee kept for decades except for three years during his military service in World War II, Lee wrote extensively for Timely, contributing to a number of different titles,

Goodman's business strategy involved having his various magazines and comic books published by a number of corporations all operating out of the same office and with the same staff,[5] One of these shell companies through which Timely Comics was published was named Marvel Comics by at least Marvel Mystery Comics #55 (May 1944), As well, some comics' covers, such as All Surprise Comics #12 (Winter 1946-47), were labeled "A Marvel Magazine" many years before Goodman would formally adopt the name in 1961,[12]

Atlas Comics

Main article: Atlas Comics (1950s)

The post-war American comic market saw superheroes falling out of fashion,[13] Goodman's comic book line dropped them for the most part and expanded into a wider variety of genres than even Timely had published, featuring horror, Westerns, humor, funny animal, men's adventure-drama, giant monster, crime, and war comics, and later adding jungle books, romance titles, espionage, and even medieval adventure, Bible stories and sports,

Goodman began using the globe logo of the Atlas News Company, the newsstand-distribution company he owned,[14] on comics cover-dated November 1951 even though another company, Kable News, continued to distribute his comics through the August 1952 issues,[15] This globe branding united a line put out by the same publisher, staff and freelancers through 59 shell companies, from Animirth Comics to Zenith Publications,[16]

Atlas, rather than innovate, took a proven route of following popular trends in television and movies—Westerns and war dramas prevailing for a time, drive-in movie monsters another time—and even other comic books, particularly the EC horror line,[17] Atlas also published a plethora of children's and teen humor titles, including Dan DeCarlo's Homer the Happy Ghost (à la Casper the Friendly Ghost) and Homer Hooper (à la Archie Andrews), Atlas unsuccessfully attempted to revive superheroes from late 1953 to mid-1954, with the Human Torch (art by Syd Shores and Dick Ayers, variously), the Sub-Mariner (drawn and most stories written by Bill Everett), and Captain America (writer Stan Lee, artist John Romita Sr,),

The Fantastic Four #1 (Nov, 1961), Cover art by Jack Kirby (penciler) and unconfirmed inker,

1960s

The first modern comic books under the Marvel Comics brand were the science-fiction anthology Journey into Mystery #69 and the teen-humor title Patsy Walker #95 (both cover dated June 1961), which each displayed an "MC" box on its cover,[18] Then, in the wake of DC Comics' success in reviving superheroes in the late 1950s and early 1960s, particularly with the Flash, Green Lantern, and other members of the team the Justice League of America, Marvel followed suit,[19] The introduction of modern Marvel's first superhero team, in The Fantastic Four #1, (Nov, 1961),[20] began establishing the company's reputation, The majority of its superhero stories were written by editor-in-chief Stan Lee, The company continued to publish a smattering of Western comics such as Rawhide Kid, humor comics such as Millie the Model, and romance comics such as Love Romances, and added the war comic Sgt, Fury and his Howling Commandos,

Editor-writer Lee and freelance artist Jack Kirby's Fantastic Four, reminiscent of the non-superpowered adventuring quartet the Challengers of the Unknown that Kirby had created for DC in 1957, originated in a Cold War culture that led their creators to revise the superhero conventions of previous eras to better reflect the psychological spirit of their age,[21] Eschewing such comic book tropes as secret identities and even costumes at first, having a monster as one of the heroes, and having its characters bicker and complain in what was later called a "superheroes in the real world" approach, the series represented a change that proved to be a great success,[22] Marvel began publishing further superhero titles featuring such heroes and antiheroes as the Hulk, Spider-Man, Thor, Ant-Man, Iron Man, the X-Men, and Daredevil, and such memorable antagonists as Doctor Doom, Magneto, Galactus, the Green Goblin, and Doctor Octopus, Lee and Steve Ditko generated the most successful new series in The Amazing Spider-Man, Marvel even lampooned itself and other comics companies in a parody comic, Not Brand Echh (a play on Marvel's dubbing of other companies as "Brand Echh", à la the then-common phrase "Brand X"),[23]

Marvel's comics had a reputation for focusing on characterization to a greater extent than most superhero comics before them,[24] This applied to The Amazing Spider-Man in particular, Its young hero suffered from self-doubt and mundane problems like any other teenager, Marvel often presents flawed superheroes, freaks, and misfits—unlike the perfect, handsome, athletic heroes found in previous traditional comic books, Some Marvel heroes looked like villains and monsters, In time, this non-traditional approach would revolutionize comic books, This naturalistic approach even extended into topical politics, Wrote comics historian Mike Benton,

In the world of [rival DC Comics'] Superman comic books, communism dd not exist, Superman rarely crossed national borders or involved himself in political disputes, ,,, From 1962 to 1965, there were more communists [Marvel Comics] than on the subscription list of Pravda, Communist agents attack Ant-Man in his laboratory on , red henchmen jump the Fantastic Four on the moon, and Viet Cong guerrillas take potshots at Iron Man,[25]

Writer Geoff Boucher in 2009 reflected that, "Superman and DC Comics instantly seemed like boring old Pat Boone; Marvel felt like The Beatles and the British Invasion, It was Kirby's artwork with its tension and psychedelia that made it perfect for the times—or was it Lee's bravado and melodrama, which was somehow insecure and brash at the same time?"[26]

Comics historian Peter Sanderson wrote that in the 1960s,

DC was the equivalent of the big Hollywood studios: After the brilliance of DC's reinvention of the superhero ,,, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, it had run into a creative drought by the decade's end, There was a new audience for comics now, and it wasn't just the little kids that traditionally had read the books, The Marvel of the 1960s was in its own way the counterpart of the French New Wave,,,, Marvel was pioneering new methods of comics storytelling and characterization, addressing more serious themes, and in the process keeping and attracting readers in their teens and beyond, Moreover, among this new generation of readers were people who wanted to write or draw comics themselves, within the new style that Marvel had pioneered, and push the creative envelope still further,[27]

The Avengers #4 (March 1964), with (from left to right), the Wasp, Giant-Man, Captain America, Iron Man, Thor and (inset) the Sub-Mariner, Cover art by Jack Kirby and George Roussos,

Lee, with his charming personality and relentless salesmanship of the company, became one of the best-known names in comics,[citation needed] His sense of humor and generally lighthearted manner became the "voice" that permeated the stories, the letters and news-pages, and the hyperbolic house ads of that era's Marvel Comics, He fostered a clubby fan-following with Lee's exaggerated depiction of the Bullpen (Lee's name for the staff) as one big, happy family, This included printed kudos to the artists, who eventually co-plotted the stories based on the busy Lee's rough synopses or even simple spoken concepts, in what became known as the Marvel Method, and contributed greatly to Marvel's product and success, Kirby in particular is generally credited for many of the cosmic ideas and characters of Fantastic Four and The Mighty Thor, such as the Watcher, the Silver Surfer and Ego the Living Planet, while Steve Ditko is recognized as the driving artistic force behind the moody atmosphere and street-level naturalism of The Amazing Spider-Man and the surreal atmosphere of the Strange Tales mystical feature "Doctor Strange", Lee, however, continues to receive credit for his well-honed skills at dialogue and sense of storytelling, for his keen hand at choosing and motivating artists and assembling creative teams, and for his uncanny ability to connect with the readers—not least through the nickname endearments he bestowed in the credits and the monthly "Bullpen Bulletins" and letters pages, giving readers humanizing hype about the likes of "Jolly Jack Kirby," "Jaunty Jim Steranko", "Rascally Roy Thomas", "Jazzy Johnny Romita", and others, right down to letterers "Swingin' Sammy Rosen" and "Adorable Artie Simek",

Lesser-known staffers during the company's growth in the 1960s (some of whom worked primarily for Marvel publisher Martin Goodman's umbrella magazine corporation) included circulation manager Johnny Hayes, subscriptions person Nancy Murphy, bookkeeper Doris Siegler, merchandising-person Charles "Chip" Goodman (son of publisher Martin), and Arthur Jeffrey, described in the December 1966 "Bullpen Bulletin" as "keeper of our MMMS [Merry Marvel Marching Society] files, guardian of our club coupons and defender of the faith",

In 1968, while selling 50 million comic books a year, company founder Goodman revised the constraining distribution arrangement with Independent News he had reached under duress during the Atlas years, allowing him now to release as many titles as demand warranted,[14] In the fall of that year he sold Marvel Comics and his other publishing businesses to the Perfect Film and Chemical Corporation, which grouped them as the subsidiary Magazine Management Company, with Goodman remaining as publisher,[28] In 1969, Goodman finally ended his distribution deal with Independent by signing with Curtis Circulation Company,[14]

1970s

In 1971, the United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare approached Marvel Comics editor-in-chief Stan Lee to do a comic book story about drug abuse, Lee agreed and wrote a three-part Spider-Man story portraying drug use as dangerous and unglamorous, However, the industry's self-censorship board, the Comics Code Authority, refused to approve the story because of the presence of narcotics, deeming the context of the story irrelevant, Lee, with Goodman's approval, published the story regardless in The Amazing Spider-Man #96-98 (May–July 1971), without the Comics Code seal, The market reacted well to the storyline, and the CCA subsequently revised the Code the same year,[29]

Howard the Duck #8 (January 1977), Cover art by Gene Colan and Steve Leialoha

Goodman retired as publisher in 1972 and installed his son, Chip, as publisher,[30] Shortly thereafter, Lee succeeded him as publisher and also became Marvel's president[30] for a brief time,[31] During his time as president, he appointed as editor-in-chief Roy Thomas, who added "Stan Lee Presents" to the opening page of each comic book,[30]

A series of new editors-in-chief oversaw the company during another slow time for the industry, Once again, Marvel attempted to diversify, and with the updating of the Comics Code achieved moderate to strong success with titles themed to horror (The Tomb of Dracula), martial arts, (Shang-Chi: Master of Kung Fu), sword-and-sorcery (Conan the Barbarian, Red Sonja), satire (Howard the Duck) and science fiction (2001: A Space Odyssey, "Killraven" in Amazing Adventures, st*r Trek, and, late in the decade, the long-running st*r Wars series), Some of these were published in larger-format black and white magazines, that targeted mature readers, under its Curtis Magazines imprint, Marvel was able to capitalize on its successful superhero comics of the previous decade by acquiring a new newsstand distributor and greatly expanding its comics line, Marvel pulled ahead of rival DC Comics in 1972, during a time when the price and format of the standard newsstand comic were in flux,[32] Goodman increased the price and size of Marvel's November 1971 cover-dated comics from 15 cents for 39 pages total to 25 cents for 52 pages, DC followed suit, but Marvel the following month dropped its comics to 20 cents for 36 pages, offering a lower-priced product with a higher distributor discount,[33]

Goodman, now disconnected from Marvel, set up a new company called Seaboard Periodicals in 1974, reviving Marvel's old Atlas name for a new Atlas Comics line, but this lasted only a year-and-a-half,[34] In the mid-1970s a decline of the newsstand distribution network affected Marvel, Cult hits such as Howard the Duck fell victim to the distribution problems, with some titles reporting low sales when in fact the first specialty comic book stores resold them at a later date,[citation needed] But by the end of the decade, Marvel's fortunes were reviving, thanks to the rise of direct market distribution—selling through those same comics-specialty stores instead of newsstands,

Marvel held its own comic book convention, Marvelcon '75, in spring 1975, and promised a Marvelcon '76, At the 1975 event, Stan Lee used a Fantastic Four panel discussion to announce that Jack Kirby, the artist co-creator of most of Marvel's signature characters, was returning to Marvel after having left in 1970 to work for rival DC Comics,[35] In October 1976, Marvel, which already licensed reprints in different countries, including the UK, created a superhero specifically for the British market, Captain Britain debuted exclusively in the UK, and later appeared in American comics,[36]

1980s

Marvel Super Heroes Secret Wars #1 (May 1984), Cover art by Mike Zeck,[37]

In 1978, Jim Shooter became Marvel's editor-in-chief, Although a controversial personality, Shooter cured many of the procedural ills at Marvel, including repeatedly missed deadlines, During Shooter's nine-year tenure as editor-in-chief, Chris Claremont and John Byrne's run on the Uncanny X-Men and Frank Miller's run on Daredevil became critical and commercial successes,[citation needed] Shooter brought Marvel into the rapidly evolving direct market,[38] institutionalized creator royalties, st*rting with the Epic Comics imprint for creator-owned material in 1982; introduced company-wide crossover story arcs with Contest of Champions and Secret Wars; and in 1986 launched the ultimately unsuccessful New Universe line to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the Marvel Comics imprint, st*r Comics, a younger-oriented line than the regular Marvel titles, was briefly successful during this period,

Despite Marvel's successes in the early 1980s, it lost ground to rival DC in the latter half of the decade as many former Marvel st*rs defected to the competitor, DC scored critical and sales victories[39] with titles and limited series such as Watchmen, Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, Crisis on Infinite Earths, Byrne's revamp of Superman, and Alan Moore's Swamp Thing,

In 1986, Marvel's parent, Marvel Entertainment Group, was sold to New World Entertainment, which within three years sold it to MacAndrews and Forbes, owned by Revlon executive Ronald Perelman,

1990s

Spider-Man #1, later renamed "Peter Parker: Spider-Man" (August 1990; second printing), Cover art by Todd McFarlane,

Marvel earned a great deal of money and recognition during the comic-book boom of the early 1990s, launching the successful 2099 line of comics set in the future (Spider-Man 2099, etc,) and the creatively daring though commercially unsuccessful Razorline imprint of superhero comics created by novelist and filmmaker Clive Barker,[40][41] Yet by the middle of the decade, the industry had slumped, and in December 1996 Marvel filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection,[42]

Marvel suffered a major blow in early 1992, when seven of its most prized artists—Todd McFarlane (known for his work on Spider-Man), Jim Lee (X-Men), Rob Liefeld (X-Force), Marc Silvestri (Wolverine), Erik Larsen (The Amazing Spider-Man), Jim Valentino (Guardians of the Galaxy), and Whilce Portacio—left to form the successful company Image Comics,[43]

Marvel's logo, circa 1990s

In late 1994, Marvel acquired the comic-book distributor Heroes World Distribution to use as its own exclusive distributor,[44] As the industry's other major publishers made exclusive distribution deals with other companies, the ripple effect resulted in the survival of only one other major distributor in North America, Diamond Comic Distributors Inc,[45][46] In early 1997, when Marvel's Heroes World endeavor failed, Diamond also forged an exclusive deal with Marvel[47]—giving the company its own section of its comics catalog Previews,[48]

Creatively and commercially, the '90s were dominated by the use of gimmickry to boost sales, such as variant covers, cover enhancements, swimsuit issues, In 1991 Marvel began selling Marvel Universe Cards with trading card maker SkyBox International, These were collectible trading cards that featured the characters and events of the Marvel Universe,

Another common Marvel practice of this period was regular company-wide crossovers that threw the universe's continuity into disarray, In 1996, Marvel had almost all its titles participate in the "Onslaught Saga", a crossover that allowed Marvel to relaunch some of its flagship characters, such as the Avengers and the Fantastic Four, in the Heroes Reborn universe, in which Marvel defectors (and now Image Comics st*rs) Jim Lee and Rob Liefeld were given permission to revamp the properties from scratch, After an initial sales bump, sales quickly declined below expected levels, and Marvel discontinued the experiment after a one-year run; the characters soon returned to the Marvel Universe proper, In 1998, the company launched the imprint Marvel Knights, taking place within Marvel continuity; helmed by soon-to-become editor-in-chief Joe Quesada, it featured tough, gritty stories showcasing such characters as the Inhumans, Black Panther and Daredevil,

In 1991 Ronald Perelman, whose company, Andrews Group, had purchased Marvel Comic's Parent corporation, Marvel Entertainment Group (MEG) in 1986, took the company public in a New York Stock Exchange stock-offering underwritten by Merrill Lynch and First Boston Corporation, Following the rapid rise of this popular stock, Perelman issued a series of junk bonds that he used to acquire other children's entertainment companies secured by MEG stock, In 1997, Toy Biz and MEG merged to end the bankruptcy forming a new corporation, Marvel Enterprises,[42] With his business partner Avi Arad, publisher Bill Jemas, and editor-in-chief Bob Harras, Toy Biz co-owner Isaac Perlmutter helped stablize the comics line,[49]

2000s

With the new millennium, Marvel Comics escaped from bankruptcy and again began diversifying its offerings, In 2001, Marvel withdrew from the Comics Code Authority and established its own Marvel Rating System for comics, The first title from this era to not have the code was X-Force #119 (October 2001), Marvel also created new imprints, such as MAX (a line intended for mature readers) and Marvel Age (developed for younger audiences), In addition, the company created an alternate universe imprint, Ultimate Marvel, that allowed the company to reboot its major titles by revising and updating its characters to introduce to a new generation,

Some of its characters have been turned into successful film franchises, such as the X-Men movie series, st*rting in 2000, and the highest grossing series Spider-Man, beginning in 2002,[50]

In a cross-promotion, the November 1, 2006, episode of the CBS soap opera The Guiding Light, titled "She's a Marvel", featured the character Harley Davidson Cooper (played by Beth Ehlers) as a superheroine named the Guiding Light,[51] The character's story continued in an eight-page backup feature, "A New Light", that appeared in several Marvel titles published November 1 and 8,[52] Also that year, Marvel created a wiki on its Web site,[53]

In late 2007 the company launched Marvel Digital Comics Unlimited, a digital archive of over 2,500 back issues available for viewing, for a monthly or annual subscription fee,[54]

In 2009 Marvel Comics closed its Open Submissions Policy, in which the company had accepted unsolicited samples from aspiring comic book artists, saying the time-consuming review process had produced no suitably professional work,[55] The same year, the company commemorated its 70th anniversary, dating to its inception as Timely Comics, by issuing the one-shot Marvel Mystery Comics 70th Anniversary Special #1 and a variety of other special issues,[56][57]

On August 31, 2009, The Walt Disney Company announced a deal to acquire Marvel Comics' parent corporation, Marvel Entertainment, for $4 billion, with Marvel shareholders to receive $30 and 0,745 Disney shares for each share of Marvel they own,[58]

While, Marvel and Disney Publishing have jointly began publishing "Disney/Pixar Presents" magazine st*rting in May 2011, there has been no announcement of a new Disney Comics imprint,[59] Marvel relaunched the CrossGen comic book imprint, owned by Disney Publishing Worldwide, in March 2011,[60]

Officers

Michael Z, Hobson Executive Vice President, Publishing [61] Group vice-president, publishing (1986)[62]

Stan Lee, executive vice-president & publisher (1986)[62]

Joseph Calamari, executive vice-president (1986)[62]

Barry Kaplan, senior vice-president, fiance and administration (1986)[62]

Jim Shooter, vice-president and Editor-in-Chief (1986)[62]

Gene J, Durante, vice-president, manufacturing and operations (1986)[62]

Harry Flynn, vice-president, Marvel Books (1986)[62]

Thomas R, Costello, vice-president , circulation (1986)[62]

Steven R, Herman, vice-president, licensing and merchandising (1986)[62]

David Fox, vice-president, legal affairs (1986)[62]

Katherine Beekman, vice-president, subscription (1986)[62]

Milton Schiffman, vice-president, production (1986)[62]

Publishers

Abraham Goodman 1939[4] – ?

Martin Goodman ? – 1972[30]

Charles "Chip" Goodman 1972[30]

Stan Lee 1972 – October 1996[30][31][61]

Shirrell Roades October 1996 – October 1998[61]

Winston Fowlkes February 1998 – November 1999[61]

Bill Jemas February 2000 – 2003[61]

Dan Buckley 2003 – present[63]

Editors-in-chief

Marvel's chief editor originally held the title of "editor", This head editor's title later became "editor-in-chief", Joe Simon was the company's first true chief editor, with publisher Martin Goodman, who had initially outsourced editorial content, having been the titular editor previously,

In 1994, Marvel briefly abolished the position, replacing Tom DeFalco with five group editors-in-chief, As Carl Potts described the 1990s editorial arrangement, "In the early '90s, Marvel had so many titles that there were three Executive Editors, each overseeing approximately 1/3 of the line, Bob Budiansky was the third Executive Editor [following the previously appointed Mark Gruenwald and Potts], We all answered to Editor-in-Chief Tom DeFalco and Publisher Mike Hobson, All three Executive Editors decided not to add our names to the already crowded credits on the Marvel titles, Therefore it wasn't easy for readers to tell which titles were produced by which Executive Editor ,,, In late '94, Marvel reorganized into a number of different publishing divisions, each with its own Editor-in-Chief,"[64] Marvel reinstated the overall editor-in-chief position in 1995 with Bob Harras,

Editor

Martin Goodman (1939–1940)[4]

Joe Simon (1940–1941)

Stan Lee (1941–1942)

Vincent Fago (acting editor during Lee's military service) (1942–1945)

Stan Lee (1945–1972)

Roy Thomas (1972–1974)

Len Wein (1974–1975)

Marv Wolfman (black-and-white magazines 1974-1975, entire line 1975-1976)

Gerry Conway (1976)

Archie Goodwin (1976–1978)

Editor-in-chief

Jim Shooter (1978–1987)

Tom DeFalco (1987–1994)

No overall; separate group editors-in-chief (1994–1995)

Mark Gruenwald, Universe (Avengers & Cosmic)

Bob Harras, Mutant

Bob Budiansky, Spider-Man

Bobbie Chase, Marvel Edge

Carl Potts, Epic Comics & general entertainment[64]

Bob Harras (1995–2000)

Joe Quesada (2000–2011)

Axel Alonso (2011–present)

Offices

Located in New York City, Marvel has been successively headquartered in the McGraw-Hill Building,[4][65] where it originated as Timely Comics in 1939; in suite 1401 of the Empire State Building;[65] at 635 Madison Avenue (the actual location, though the comic books' indicia listed the parent publishing-company's address of 625 Madison Ave,);[65] 575 Madison Avenue;[65] 387 Park Avenue South;[65] 10 East 40th Street;[65] 417 Fifth Avenue;[65] and a 60,000-square-foot (5,600 m2) space at 135 W, 50th Street,[66][67]

Marvel characters in other media

Marvel characters and stories have been adapted to many other media, Some of these adaptations were produced by Marvel Comics and its sister company, Marvel Studios, while others were produced by companies licensing Marvel material,

Films

Main article: List of films based on Marvel Comics

Main article: Marvel Studios

Prose novels

Main article: Marvel Books

Marvel first licensed two prose novels to Bantam Books, who printed The Avengers Battle the Earth Wrecker by Otto Binder (1967) and Captain America: The Great Gold Steal by Ted White (1968), Various publishers took up the licenses from 1978 to 2002, Also, with the various licensed films being released beginning in 1997, various publishers put out movie novelizations,[68] In 2003, following publication of the prose young adult novel Mary Jane, st*rring Mary Jane Watson from the Spider-Man mythos, Marvel announced the formation of the publishing imprint Marvel Press,[69] However, Marvel moved back to licensing with Pocket Books from 2005 to 2008,[68] With few books issued under the imprint, Marvel and Disney Books Group relaunched Marvel Press in 2011 with the Marvel Origin Storybooks line,[70]

Television programs

Main article: List of television series based on Marvel Comics

Many television series, both live-action and animated, have based their productions on Marvel Comics characters, These include multiple series for popular characters such as Spider-Man and the X-Men, Additionally, a handful of television movies based on Marvel Comics characters have been made,